“We cannot begin to know ourselves until we can see the real reasons why we do the things we do, and we cannot be ourselves until our actions correspond to our intentions.”

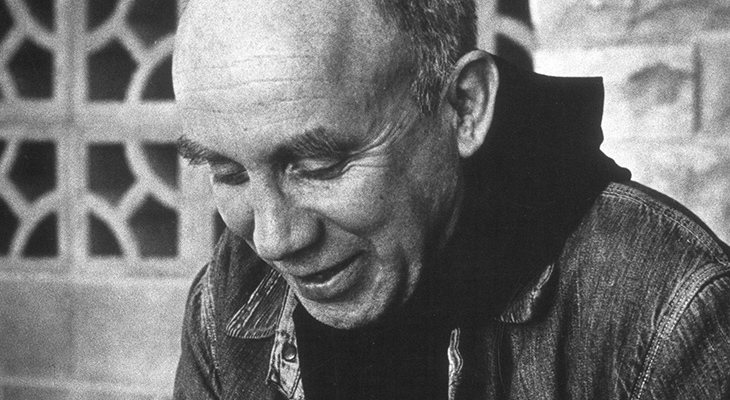

Thomas Merton, No Man Is An Island

The next time one of my children attempts to rationalize one his actions with the emotionally charged retort, “but I didn’t mean to!”, I’m going to give him some slack. In the past it has been easy for me to say, “I don’t care what you meant, I care what you did.” As Aristotle says, “you are what you repeatedly do,” not, “you are what you repeatedly intend to do.” While I still believe this is true, our intentions are play a crucial role in the what we repeatedly do.

In some cases, intentions can radically define the actions. This is particularly important to note when one is attempting to convince his wife that he did not throw her tulip bulbs away as a payback for burning dinner. I threw them away because I mistook them for old leftovers. While it is one act, the intentions significantly change the meaning of that act.

I am used to thinking about intentions when it comes to clarifying past actions to someone who might have misunderstood me, but I am beginning to appreciate the importance of identifying my intentions at the forefront of many of my choices and actions. Actions are not merely actions, but more often than not our actions are like scenes in a much larger movie. Every scene of a good movie fits within the larger narrative of that movie because it is connected by themes, plot structure, continuity, foreshadowing, flashbacks, etc. The main reason scenes get edited out of movies is because that particular scene does not contribute to the larger narrative.

So here’s the scene I offer you: My elderly neighbor often needs help with various things around her house, as well as assistance with the occasional problems and situations that pop up on a regular basis. What should I do? For instance, she wants my help in buying a new car. Should I help her and why? For some people it is enough to simply help out because “it’s the right thing to do.” But this overlooks the importance of intention. What would you think about my actions if I told you that the reason I am helping her is because I want her to include me in her will? This particular woman is indeed filthy rich, so this is a very real possibility. Is my action “good,” even though my intentions are questionable?

One way to answer this is to clarify a bit about what we mean by intention. According to Aquinas, “moral acts take their species according to what is intended, and not according to what is beside the intention” (ST II-II q. 64 a. 7). In other words, what defines my conscious actions is the intention behind that action. What do I hope will follow from this particular act? And according to both Aquinas and Aristotle, this act should move me closer to what I believe to be the ultimate good.

For some reason this particular insight on the significance of intentions has hit me in a peculiar way. I have always known that intentions are important to keep in check, and that it is not enough to do the right thing, but we must do the right thing for the right reasons. However, I was still holding onto the assumption that even if you are not doing the right thing for the right reason, you are halfway there because you are at least still doing a good thing. But I’m not so sure anymore. If we take Aristotle and Aquinas seriously (which I am wont to do), then what makes the action good IS the intention. The next question I feel compelled to ask myself is how intentional are my everyday actions and decisions? How often do I habitually act? Where those habits formed with the right intentions in mind?

It is all too easy to do think that there are good actions in and of themselves, as if their goodness is self-contained and unconnected to their intentions or end goals. It is easy to assume that helping my neighbor is good regardless if I have good intentions or virtuous expectations. But this might be what Paul has in mind when he says, “So, whether you eat or drink, or whatever you do, do everything for the glory of God. (I Corinthians 10:31) and Colossians 3:17 “And whatever you do, in word or deed, do everything in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through him.”

“An act without purpose lacks something of the perfection of freedom, because freedom is more than a matter of aimless choice. It is not enough to affirm my liberty by choosing ‘something.’ I must use and develop my freedom by choosing something good.”

Thomas Merton, No Man is an Island